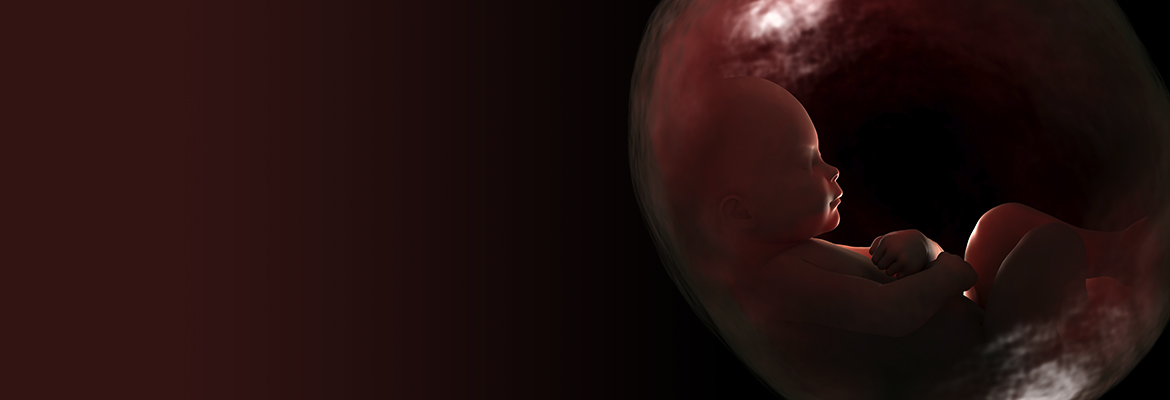

Four years ago, spurred by the desire to give premature babies a better chance for a healthy life, a team of multidisciplinary researchers at CHOP began to develop a fluid-filled system that would imitate life for a fetus in the womb. Containing the necessary nutrients that a fetus requires to develop and thrive, the environment would support and stabilize babies born too soon, particularly between 23 and 26 weeks. Because extremely premature infants often have underdeveloped lungs that cannot adapt to gas ventilation, the system would give them a valuable few weeks to mature these and other vital organs — just as if they were still being carried in their mother’s uterus.

The research team led by Alan Flake, MD, fetal surgeon at CHOP, reported on their most recent prototype in Nature Communications. The study captivated both the scientific community and the mainstream media as it described how the current preclinical model supported eight fetal lambs for as long as 28 days, keeping them healthy as indicated by vital signs, blood flow, fetal blood gases, and other parameters monitored 24 hours a day.

“This system is potentially far superior to what hospitals can currently do for a 23-week-old baby born at the cusp of viability,” said Dr. Flake who is also a professor of Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “This could establish a new standard of care for this subset of extremely premature infants.”

After four rounds of prototypes, the current system is a sealed, sterile, fluid-filled container custom-made to fit each fetus and insulated from fluctuations in temperature, pressure, light, and hazardous infections. It provides nutrients and growth factors to each fetal lamb through a continuous amniotic fluid exchange system developed by Marcus Davey, PhD, a fetal physiologist at CHOP and associate professor of Surgery at Penn. Meanwhile, the lamb’s heart pumps blood via its umbilical cord into a low-resistance external oxygenator that substitutes for the mother’s placenta. Mimicking the normal physiology of a fetus, this flow of blood is driven entirely by the fetal lamb itself.

While the system has only been tested in animals, Dr. Flake believes that if more research shows that the system can translate into clinical care, it could help reduce mortality and disability for extremely premature babies by bridging their time from the womb to the world.